Grace Notes

When Bob Dylan popularized folk music during the Folk Revival that stretched from the 1940s to the 1960s, he was labeled “the voice of a generation.” But as Ellen Chase Harper (PhD, Education, 1996) explains in her recently published book, Always a Song: Singers, Songwriters, Sinners & Saints—My Story of the Folk Music Revival, the traditional view of folk music was: “You don’t write folk songs…you discover them.”

Harper has led a life of such discovery. She often wrote, she said, but never with the belief that her stories would be published for others to read. Instead, she wrote for herself as a means to cope with something upsetting or to document a funny situation. Likewise, she wrote for her boys, so they would understand what their grandparents had overcome.

Harper had a collection of stories written down, some on scraps of paper, others in spiral notebooks. As she calls them, these discreet stories included recollections from childhood, days from early motherhood, and important historical references to when her parents established the Folk Music Center in Claremont.

“I started writing when I realized my boys didn’t know about the Folk Music Center or how it came to be or why,” Harper recalled.

So, she gathered her stories and began sharing them with her sons Ben, Joel, and Peter. To her delight, they loved them. At Joel’s suggestion—he had already published a popular children’s book—she sent some stories to a publisher, who liked them, but nothing happened.

A year went by before she heard from him again: Mark Tauber had moved to Chronicle Books and remembered her stories from the year before. Harper was thrilled when he offered to publish them and equally overwhelmed by his requirement that she organize them into a memoir.

Writer Sam Barry came on board, providing what she describes as “generational comfort.” Barry is himself a musician, and he plays piano and harmonica for Rock Bottom Remainders, a rock band whose members are all authors, including his brother Dave Barry, a nationally syndicated humor columnist. Sam Barry knew the era, understood the music, and is the author of several columns and books, including How to Play the Harmonica: And Other Life Lessons.

“We were trying to tie stories together, but they crisscrossed time,” she said. “It seemed best to just start from the beginning.”

Indelible Scars

Always a Song begins, quite literally, at the beginning of Harper’s life. Her parents, Charles and Dottie Chase, met and married in the late 1930s. Charles and Dot were independent thinkers. She played banjo and taught music lessons; he was a math and English teacher at a local high school in Quincy, Mass., and spent much of his free time repairing instruments.

When Harper was a child, her family, which includes three sisters, Sue, Joanne, and Sally, was blacklisted for their father’s association with the Communist Party. As a result, her father lost his teaching job, and a special commission was assembled to investigate his activities.

“I was raised to be aware of the underdog and raised to comprehend inequalities,” Harper shared. “When you have that awareness, you can’t really set it aside.”

Being ostracized by her small community in North Weymouth, Massachusetts, left indelible scars. Friends disappeared, classmates harassed and called her names, and invitations to birthday parties ceased. But there was no room for self-pity in the Chase home, Harper said, so she did the only thing she knew to do: Fight back.

“I would have rather been alone than to have lived with that threat,” she said. “What would have happened to me if I couldn’t fight back?”

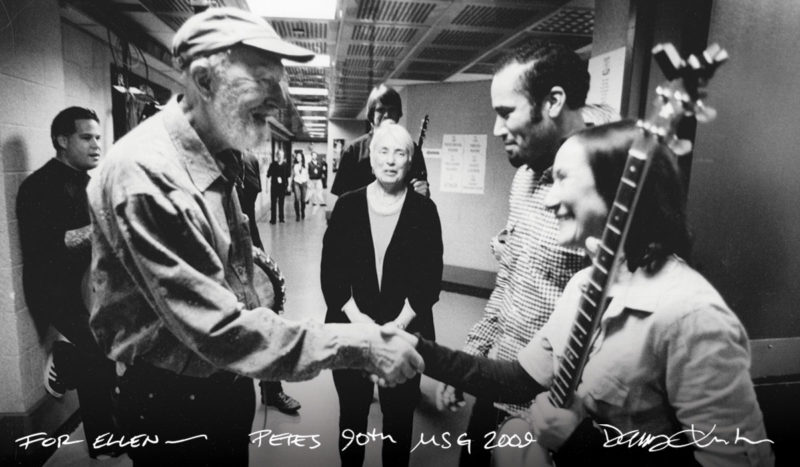

The family settled in Claremont in the 1950s with their village home playing host to some of the most famous musicians of the time. Brothers Pete and Mike Seeger were family friends, and Joan Baez was a regular visitor to the family’s Seventh Street home. Harper’s brushes with celebrity were numerous. She and her parents met Bob Dylan after a concert at The Gym at the University of California, Riverside, and Jimi Hendrix once kissed her teenage hand.

Yet Harper remains mostly unfazed by celebrity. Instead, her life is largely shaped by her experiences of social injustice. Harper has terrible memories of her childhood in Weymouth when classmates looked for her “Jew horns,” and she recalls working tirelessly in Claremont to assimilate by ridding herself of her Boston accent.

I was raised to be aware of the underdog and raised to comprehend inequalities. When you have that awareness, you can’t really set it aside.” — Ellen Harper

Squarely facing adversity continued through adulthood. One could almost say Harper’s life choices kept her in the eye of the political storm—she’s a feminist, a female guitarist, and a banjoist. She also married and, after time, divorced a Black man during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Later, she would become a graduate student as a single mother with three young sons.

Her then-husband, Leonard Harper, was an administrator working to increase diversity at the Claremont Colleges, but even with their connections in Claremont, the young couple struggled to find housing.

“Claremont real estate agents at the time were really racist,” she recalled. “They told us to our face they would never rent to a mixed-race couple.”

Through it all, playing and teaching music was her refuge. She followed her mother’s lead in teaching at the Folk Music Center, spending most of her teens and early adulthood offering guitar and banjo lessons in the family store while organizing musical performances at their second Claremont location, The Golden Ring. She loved it, but she wanted more.

Educator & Musician

With her boys in high school, Harper enrolled in the Teacher Education Internship Program at Claremont Graduate University.

Her father Charles had attended CGU in the late 1950s. His acceptance had included a panel review of his involvement with the Communist Party in Massachusetts. Harper understood CGU as a progressive institution for the most part, and her father had excelled in the teacher program. He was even invited to join the Faculty Club. Unfortunately, this elite society did not allow women as members at the time, so he declined.

Harper’s years at CGU were some of the best of her life, she said. Drawing from her childhood, her PhD dissertation was titled “Teaching With the Enemy: An Archival and Narrative Analysis of McCarthyism in the Public Schools.”

She not only has a remarkable memory of the events that shaped her life, she fully digests these experiences, using adversity as inspiration. During her studies at CGU, she had an internship with the Pomona Unified School District in a bilingual second-grade classroom.

“For the first time in decades, music is not part of my professional life, and I crave it,” she writes in Always a Song. “I bring my guitar to the classroom, and we sing first thing in the morning in English and Spanish. We sing seasonal songs, holiday songs, family songs, and activity songs. For Black History Month, I teach them songs from the Civil Rights Movement.”

After the school’s principal reduced the students’ lunch break by five minutes, Harper’s class, inspired by the folk songs she had taught them, conducted a sit-in to protest.

“When the bell rang for dismissal, they didn’t leave,” she writes. “The principal was summoned, and a couple of brave girls started singing the old Civil Rights Movement anthem I taught them, ‘We Shall Not Be Moved.’ The entire class joined in, singing first in English, then in Spanish.”

Art & Activism: The Family Business

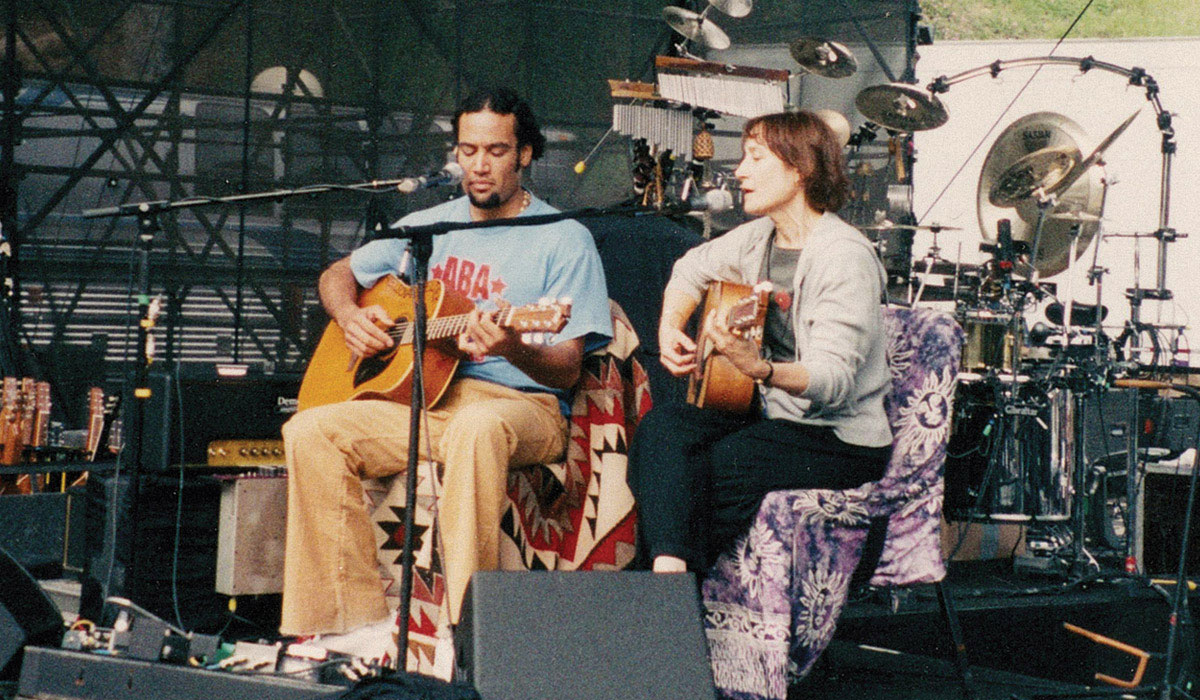

Harper enlightened her students as she had her three sons. Her oldest, Ben Harper, is a Grammy Award-winning musician well recognized for his activism.

Middle son Joel Harper is a musician who also manages his own publishing house. He is the author of several books, including All the Way to the Ocean, inspiring children to protect the marine environment and stop pollution from entering storm drains and local waterways.

Her youngest, Peter Harper, is a sculptor and professor of art at California State University, Channel Islands. He is also a touring musician and is active with the Surfrider Foundation.

For their collective efforts toward environmental protection, the Surf Industry Manufacturers Association recently named the brothers Environmentalists of the Year.

Harper is keenly aware of the problems plaguing our country—over-commercialism, wealth disparity, and, perhaps most significantly, racism. But even with first-hand accounts of political exile and blatant racism in her own life, Harper admits she doesn’t have answers.

“We need leaders. Movements generate leaders,” Harper said. “Maybe it’s the education system? How do we fix it?”

One obvious answer, she believes, may be simple enough to achieve—talking to one another.

“When my father had the store on First Street, the owner of Bud’s Bike Shop was conservative,” she shared. “But they helped each other. They worked together and talked for hours. That couldn’t happen today. It’s so tribal now.”

Always a Song, by Harper and Sam Barry with a foreword by her son Ben Harper, is available on Amazon, through the publisher Chronicle Books, at the Folk Music Center, 220 N. Yale Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711, or at folkmusiccenter.com.

Kathryn Dunn is a freelance writer and the former editor of the Claremont Courier.