Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Back in the 1950s, when Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi was 16 and traveling in Switzerland (but with no money to enjoy skiing or even go to a movie), he heard about a free lecture in Zurich. The lecture was on the topic of flying saucers.

It sounded entertaining to him, he told a TED audience in 2004. Since it was free, he decided to go.

The man he heard that night didn’t talk about aliens from outer space. He spoke about how the psyches of Europeans had been so deeply traumatized by World War II that they projected UFOs into the skies.

It was a coping mechanism, the man said, a way of finding order in the inexplainable chaos of war.

Csikszentmihalyi had no idea that the lecturer that night was Carl Jung—but hearing Jung stayed with him long after he moved to the United States at the age of 22. He’d witnessed that wartime trauma himself—his own family suffered the loss of his two older brothers—and it instilled in him a deep desire to study psychology and understand what a meaningful life can be.

That inquiry into life’s meaning and purpose resulted in an acclaimed professional career that, over many years, garnered him much praise and attention as a founder of the popular and growing field of positive psychology and as the “father of flow,” which refers to the optimal psychological state when one is fully immersed in an activity.

This fall the CGU community mourned the loss of this pioneering figure known fondly on campus as “Mike C.” According to a message posted on Facebook by the family, Csikszentmihalyi died on October 20, surrounded by his family in his Claremont home. Isabella, his wife of 60 years, was at his bedside. He was 87.

Reactions: On-Campus and Beyond

CGU President Len Jessup and School of Social Science, Policy & Evaluation (SSSPE) Dean Michelle Bligh delivered the sad news of Mike’s passing in messages to the entire university community as well as to the members of the Division of Organizational & Behavioral Sciences (DBOS).

He was one of the most present people I knew. He’d just listen to you, and he was in the moment, in the flow, and I think that’s because he’d studied it for so long and knew how to live life in that optimal state.” — Stewart Donaldson

For CGU’s Stewart Donaldson, who worked with Csikszentmihalyi to create the university’s trailblazing program in positive psychology, the news was still a shock even though he knew Mike had been ailing in recent years.

He said it felt like losing a parent.

“I haven’t felt this low since my dad died,” said Donaldson, who is a University Distinguished Professor and directs the Claremont Evaluation Center. “He was such a trustworthy friend, and I learned so much from him. He was one of the most present people I knew. He’d just listen to you, and he was in the moment, in the flow, and I think that’s because he’d studied it for so long and knew how to live life in that optimal state.”

Word also spread to many beyond campus, including Martin Seligman, Emeritus Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. Seligman co-founded the field of positive psychology with Mike in the late 1990s.

Seligman, who received the news as his first grandson was being born, said it plunged him into “the profoundest grief at losing my colleague and friend Mike” even as he was experiencing the elation of becoming a grandparent.

Similar sentiments were expressed on social media by former colleagues and students and in the Hungarian press. Boing Boing referred to him as “legendary”; The Budapest Times and Hungary Today hailed him as the “Flow Theory Architect.” Hungary Daily News celebrated his career and called him a psychologist “whose theory conquered the world.”

Early Years, Move to Claremont

Born in 1934 in Fiume, Italy (now Rijeka, Croatia), Csikszentmihalyi was the son of Hungarian diplomat Alfred Csikszentmihalyi (né Hausenblasz) and Edith Jankovich de Jeszenicze. As a refugee in postwar Rome, he attended the Classical Gymnasium Torquato Tasso and developed a deep interest in psychology.

In 1956, he moved to the United States to study psychology at the University of Chicago and wrote his doctoral dissertation on artistic creativity with creativity scholar Jacob W. Getzels. During that time, he met Isabella Selega, a graduate student in Russian history. They married in 1961, and Csikszentmihalyi taught at Illinois’ Lake Forest College before joining the Chicago faculty in 1971.

In the 1990s, with his retirement from Chicago, the Drucker School’s Jean Lipman Blumen recruited him to come to Claremont and teach psychology and management. With his arrival and with the droves of psychology students that headed down to his Drucker office, it was clear that something special was happening on campus. So, when he was given an offer from USC to start his own program, Donaldson said he asked Mike to stay and do it at CGU instead under the auspices of DBOS. Mike agreed.

Together, Donaldson recalled, they thought that their positive psychology program would simply be a small concentration that would fit with the division’s other programs, but, he added, “it just took off and, many hundreds of graduates later, it has taken on an incredible life all of its own.”

‘Flow,’ Innovations, Publications, and Awards

Csikszentmihalyi is best known for his work on the concept of “Flow,” which describes a state of optimal experience in which one’s skills match the challenges of a situation, and for his role as a founder of positive psychology.

Underlying much of this work was his innovative and groundbreaking use of pagers and questionnaires to produce a database based on people’s self-reports of their ordinary experiences.

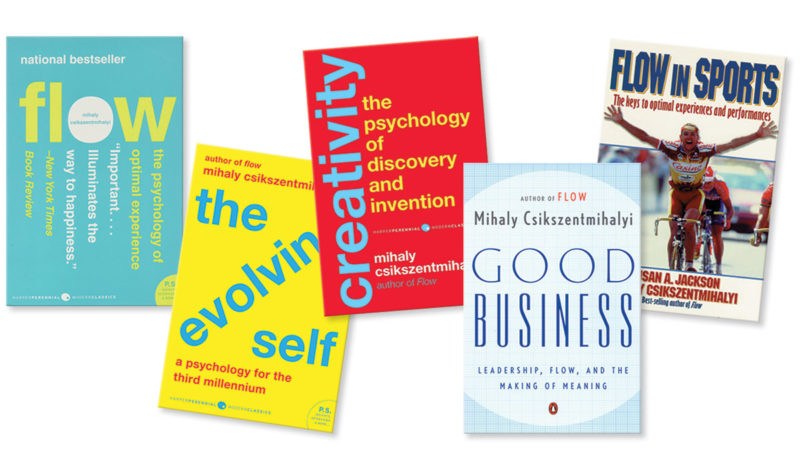

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience became a bestseller in 1990, which presented his conclusions based on that database in a warm, humanistic prose style. His other books, The Evolving Self (1993), Creativity (1996), and Good Business (2003), expanded on his theories in a variety of directions.

Because Csikszentmihalyi’s approach generated a cross-section of daily experience, his analysis paid more attention to experiences of positive states—like enjoyment or creativity—than many of his predecessors. That work formed the theoretical background of his collaboration with Seligman.

Together, in 2000, they published an influential article in American Psychologist, the flagship journal of the American Psychological Association, that introduced the profession to positive psychology. That work was recognized with Csikszentmihalyi’s appointment as a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and his selection for the 2009 Clifton Strengths Prize and the 2011 Széchenyi Prize.

Seligman—who served as the APA’s president in 1998—recalled how he asked Mike to join him in writing their pioneering journal article.

“Mike had played such an enormous role in helping me prepare my theme for the APA presidency,” he recalled, “that I prevailed on him to be the joint author of that article.”

Other awards and distinctions include his receipt, in 2014, of the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary. Csikszentmihalyi also has enjoyed a robust following online; Since the first appearance of his 2004 TED Talk, “Flow, the secret to happiness,” it has received some 6,693,254 views.

Honoring a Native Son

When they created CGU’s positive psychology program, Donaldson said he knew Csikszentmihalyi was an important figure in psychology. However, he didn’t fully understand the international dimensions of that reputation until they attended a European Positive Psychology conference in 2008 held not far from Csikszentmihalyi’s birthplace of Rijeka.

When they arrived at their hotel, Donaldson recalled, “there were cameras everywhere and all these people looking for him. Later, when I was walking around the conference, people kept coming up and asking, ‘Where is he? I saved all my money so I could travel here and meet him!’ It was really incredible.”

When Csikszentmihalyi took the stage during the conference, he received a standing ovation before he even began

“The audience’s reaction had this real rock star feel to it,” Donaldson said. “Here was this famous person from their region, and everyone looked up to him. I didn’t have a true sense of Mike’s international impact until that moment.”

Lessons and Legacy

With his arrival at CGU in 1999, Csikszentmihalyi founded the Quality of Life Research Center (QLRC) with colleague and co-director Jeanne Nakamura.

One result of Csikszentmihalyi’s work with Seligman on the field of positive psychology was to create several research centers across the country that would focus on the principles of this fledgling field. The goal was to help raise its visibility on university campuses. The QLRC was one of these.

[Students appreciated] not just Mike’s creativity, intellect, and wisdom, but also his humor, warmth, and generosity— he could be unstinting with his time and attention. Visitors to the QLRC were often awed by this.” — Jeanne Nakamura

“I am constantly and keenly aware of what a unique and fulfilling privilege it has been to work with Mike in so many capacities here at CGU for the past two decades,” said Nakamura, who is an associate professor of psychology in the university’s Division of Behavioral & Organizational Sciences.

For Nakamura, Csikszentmihalyi was always giving with his time and support to anyone entering the QLRC offices on Dartmouth Avenue. He didn’t have to know them well; he was generous with friends and strangers alike.

That made a deep impression on students, Nakamura noted, and they appreciated “not just Mike’s creativity, intellect, and wisdom but also his humor, warmth, and generosity— he could be unstinting with his time and attention. Visitors to the QLRC were often awed by this.”

Over the years, he continued his research and worked on books and articles. As a result, he has been cited often in many places, from the top journals of his discipline to the pages of Forbes and the New York Times.

Despite a considerable reputation, Csikszentmihalyi was deeply humble with a low-key style of presentation that put students and colleagues alike at ease. Donaldson said it was “one of Mike’s beliefs that his own pursuit of happiness shouldn’t interfere with other people’s pursuits to be happy.” He also displayed a sharp sense of humor, often making absurd or ironic comments in a deliberately deadpan, impassive manner.

Donaldson said he had an opportunity to see Csikszentmihalyi about a year ago before his health deteriorated. He seemed satisfied with his achievements and what might be considered his legacy.

“So often people look back on their lives and express all these regrets about what they wished they could have done. Mike wasn’t like that,” Donaldson said. “He said he couldn’t have imagined living his life any other way. He created an environment on campus where people could train to have a positive impact on the world, and he felt really good about that. He was so pleased to see our program develop and grow, knowing it would live on.”

***

Mike C is survived by his wife Isabella and their sons, Mark and Christopher, who teach at UC-Berkeley and Cornell University, respectively. He is also survived by their respective partners Annie Hope and Gemma Rodrigues, and grandchildren Emily Isabella, Henry Stephen, Kinga Jane, Aschalew, Zofia Rose, and Iris Althea Diana Isabella.

The family requests that any contributions be made to the Center for Biological Diversity or Habitat for Humanity.